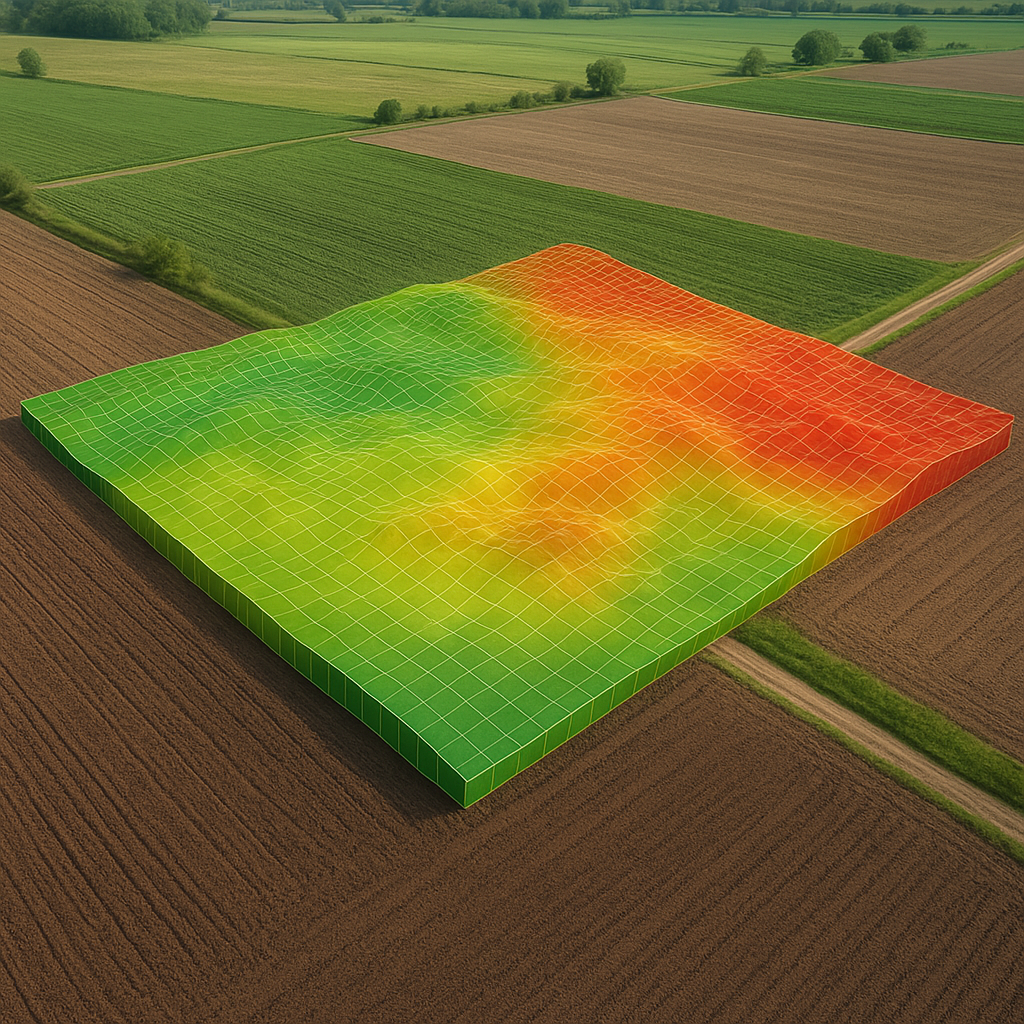

Advancements in 3D soil mapping are transforming the way agronomists, planners, and farmers approach land management. By integrating geospatial information, advanced modeling techniques, and on-site sensor data, a comprehensive picture of the soil structure emerges. This enables stakeholders to optimize resource allocation, improve crop yields, and promote sustainable land use.

3D Soil Mapping: Principles and Technologies

The foundation of 3D soil mapping lies in combining traditional soil surveys with modern digital tools. Remote sensing platforms, such as satellites and drones equipped with multispectral and hyperspectral sensors, acquire surface reflectance data that correlate with soil properties. Ground-based sensors—electrical conductivity probes, penetrometers, and neutron probes—offer direct measurements of subsurface characteristics. After data collection, geostatistical techniques like kriging or machine learning algorithms generate spatially continuous volumetric models.

Key technological components include:

- Geophysical surveys: Providing resistivity or seismic velocity data for layer identification.

- LiDAR and photogrammetry: Capturing microtopography, erosion patterns, and surface roughness.

- Geovisualization software: Enabling interactive 3D rendering of soil horizons and attribute distributions.

- GIS-based platforms: Integrating multiple datasets to support dynamic queries and scenario analysis.

Through automated workflows, raw measurements transform into detailed maps of soil texture, bulk density, moisture retention, and nutrient availability. These volumetric datasets reveal hidden patterns below the plowlayer, guiding decisions on irrigation, fertilization, and field drainage.

Applications in Land Use Planning and Agriculture

Optimizing land use demands a thorough understanding of subsurface variability. 3D soil maps contribute to:

- Precision agriculture: Variable-rate application of seeds, fertilizers, and amendments tailored to soil heterogeneity.

- Erosion risk assessment: Identifying slopes and soil textures prone to runoff and gully formation.

- Infrastructure siting: Locating roads, storage facilities, and drainage ditches in zones with stable subsurface support.

- Land capability classification: Assigning fields to crop systems based on water-holding capacity and root penetration depth.

For example, farmers can leverage 3D models to optimize irrigation systems. By visualizing infiltration rates at various depths, they design zoning maps that reduce water waste and mitigate waterlogging. Similarly, nutrient management plans incorporate vertical profiles of nitrogen retention, helping to avoid leaching into groundwater and lowering fertilizer costs.

In urban fringe regions, planners utilize these maps to designate green zones, protect high-value soils, and balance competing demands between agriculture, development, and conservation. The volumetric perspective ensures that infrastructure projects do not disrupt critical soil layers essential for crop growth or aquifer recharge.

Case Studies: Demonstrations of Impact

Several pilot projects have showcased the transformative power of 3D soil mapping. In the Midwestern United States, a large-scale farm adopted electromagnetic surveys combined with yield monitor records. The resulting model pinpointed low-yield areas correlated with compacted layers. By implementing deep tillage only in targeted zones, operators cut fuel usage by 20% and increased average yield by 8% in the first season.

In Australia’s grain belt, researchers used drone-based photogrammetry to map micro-relief and surface crusts. When merged with proximal gamma-ray spectrometry data, they produced a 3D map of clay distribution. This guided machinery traffic patterns, reducing topsoil compaction in sensitive paddocks and preserving productivity over repeated seasons.

Meanwhile, European vineyards have begun applying 3D soil analyses to fine-tune canopy management. By correlating vine vigor with subsurface moisture reserves, vintners adjust row orientation and pruning intensity. The result: more consistent grape quality and enhanced terroir expression in premium wine batches.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite clear benefits, challenges persist. High-resolution data acquisition can be costly for smallholders. Sensor calibration, data processing expertise, and the need for interoperable software platforms may pose barriers. Data privacy and ownership questions also arise when multiple stakeholders contribute to shared mapping efforts.

Ongoing research focuses on reducing costs through low-altitude UAV swarms, affordable open-source software, and machine learning models requiring minimal ground truth points. Advances in soil spectroscopy will further refine non-invasive measurement of organic matter and trace elements. Integration of temporal monitoring—repeated 3D scans over seasons—promises dynamic soil health tracking, capturing changes due to erosion, management practices, and climate variability.

Collaborative initiatives between universities, ag-tech startups, and government agencies aim to democratize 3D mapping services. By offering cloud-based platforms with intuitive interfaces, they empower agronomists and farmers to generate high-value maps without steep learning curves.

Conclusion

Embracing 3D soil mapping heralds a new era in sustainability and productivity. The integration of volumetric soil data into land use planning and precision agriculture unlocks unprecedented insight into subsurface dynamics. As technology matures and becomes more accessible, stakeholders across the rural-urban spectrum stand to benefit from data-driven decisions that preserve resources, enhance yields, and foster resilient landscapes.